By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

Under-the-radar amendments to two bills that passed in the final days of the 2021 legislative session are intended to make law enforcement agencies in Colorado more transparent and accountable.

One change will impact the release of body-worn and dashboard camera footage, and another might help mitigate the loss of public information caused by the encryption of police radio transmissions. Two additional provisions address public access to records of completed police internal affairs investigations and lists of officers who have credibility issues.

Internal affairs files. Before House Bill 19-1119 went into effect in April 2019, nearly all sheriff’s offices and police departments in Colorado routinely rejected requests for internal affairs files, either with a blanket policy or a finding that disclosure would be “contrary to the public interest.”

The new law established a statewide standard for the disclosure of IA records. But its scope is limited, as the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition pointed out in an article last year. Many law enforcement agencies adhere strictly to language in the statute which requires them to release only records “related to a specific, identifiable incident of alleged misconduct involving a member of the public” while an officer is in uniform or on duty.

Because the law is worded that way, it doesn’t guarantee the public will see the disciplinary history of a controversial officer or the results of internal investigations that weren’t publicly announced. Journalists who requested summaries of IA investigations from the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office, the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office and the Fort Collins and Loveland police departments were told their requests were too “vague” or did not “meet the specificity” required by the law.

“You have to know about a specific incident to request the records,” Denver Post reporter Elise Schmelzer told CFOIC in 2020. “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

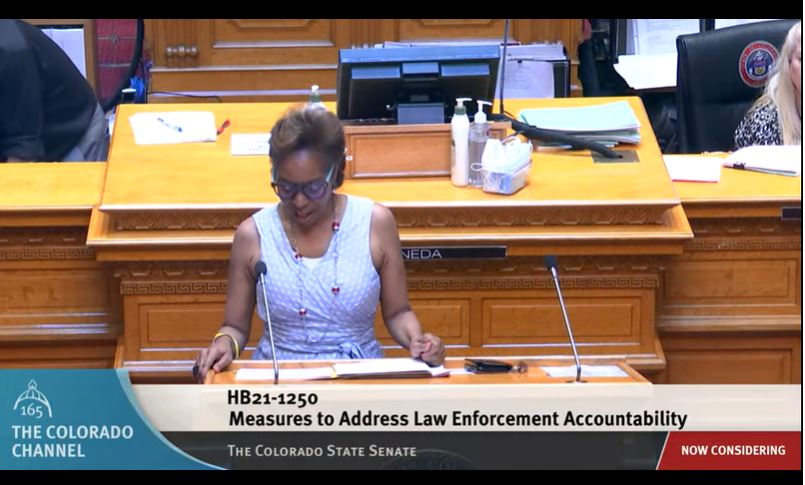

But a tiny amendment to House Bill 21-1250, a bipartisan follow-up to the sweeping police accountability bill passed in 2020, will “help the public access any of these files related to potential misconduct,” said Sen. Julie Gonzales, D-Denver, during a Senate State, Veterans and Military Affairs Committee hearing. The amendment removes the phrase “specific, identifiable” before the word “incident.” Assuming the bill is signed into law, this provision in the Colorado Criminal Justice Records Act (CCJRA) will open for public inspection records of completed IA investigations related to “an incident of alleged misconduct involving a member of the public.”

It remains to be seen whether law enforcement agencies statewide will now follow the lead of the Denver Department of Public Safety, which regularly provides the disciplinary records of police officers and sheriff’s deputies in response to requests.

Agencies may still be able to withhold internal affairs records unrelated to interactions with the public. But they would have to show why disclosure would be “contrary to the public interest” after conducting a balancing test of factors laid out in a 2005 Colorado Supreme Court ruling.

Brady lists. Last December, The Denver Post showed that district attorneys’ offices around the state take an uneven approach to publicly disclosing the names of law enforcement officers “with criminal convictions, histories of lying, excessive force incidents or other backgrounds that could impact their credibility in court.” Just nine of 22 DAs’ offices provided their Brady lists, which are named for a 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said prosecutors cannot withhold evidence that is favorable to a defendant.

Under an amendment to Senate Bill 21-174, however, public disclosure will be mandatory. The bipartisan bill establishes a committee to develop model policies and procedures for law enforcement agencies and DAs to follow when an officer’s credibility is called into question. By Feb. 1, 2022, each district attorney’s office must make its Brady list policies and procedures available to the public.

The policies and procedures must also “describe how members of the public can access” a database of peace officers who are subject to credibility disclosure notifications. By 2022, the state’s Peace Officers Standards and Training (POST) board is supposed to create and maintain the database “in a searchable format to be published on its website.” Funding for the database, however, is “subject to available appropriations.”

“This (will be) much more in the public eye than it is currently,” said Rep. Shannon Bird, D-Westminster, who sponsored the bill with Republican Sen. John Cooke, R-Greeley, Sen. Joann Ginal, D-Fort Collins, and Rep. Terri Carver, R-Colorado Springs.

Body-cam footage. Senate Bill 20-217, the law enforcement accountability law enacted last year, set requirements for the public release of body-worn and dashboard camera footage that were to go into effect July 1, 2023. Under an amendment to HB 21-1250, which the House repassed Tuesday, the footage-release provision will go into effect upon the governor’s signature on the bill.

Unedited video and audio recordings of incidents “in which there is a complaint of peace officer misconduct” will have to be released within 21 days after a request for the recordings or up to 45 days from the date of the allegation of misconduct if the video “would substantially interfere with or jeopardize an active or ongoing investigation.” A prosecuting attorney must explain in writing why the delayed release is justified; that statement will have to be released to the public when the video is released.

Under current law, law enforcement agencies can use the discretion afforded them by the CCJRA to delay the release of footage or disclose only certain portions.

Agencies not yet equipped with body-worn cameras will be required under HB 21-1250 to provide them to all officers who interact with the public by July 1, 2023.

Police radio encryption. Another amendment to HB 21-1250 addresses the trend among Colorado law enforcement agencies, including the Denver and Aurora police departments, to completely encrypt their radio traffic. It follows unsuccessful bills on this issue in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

The final version of the amendment requires an agency that fully encrypts radio transmissions to create a policy for allowing — through agreements — news media access to “primary dispatch channels or talk groups” via commercially available radios or scanners. The policy may include verification of media credentials, provisions related to the cost of providing radio receivers or scanners and “reasonable restrictions” on the use of the equipment.

Because the amendment does not define “reasonable restrictions,” it remains to be seen whether it will lead to agreements between news organizations and certain agencies, such as the Denver Police Department, that have insisted on indemnity clauses and other provisions deemed unacceptable by news organizations.

More than 30 law enforcement agencies in Colorado have encrypted their radio communications, making it harder for journalists to cover breaking news and quickly let the public know about potentially hazardous incidents.

Police officials have said encryption is necessary to protect victims’ privacy and officer safety because criminals have been known to monitor radio traffic.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.