By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

In mid-August, when Carolyn Bedingfield requested copies of emails from a public charter school in El Paso County, she made sure to ask that any records kept in an electronic format be provided to her in an electronic format, as a 2017 amendment to the Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) requires.

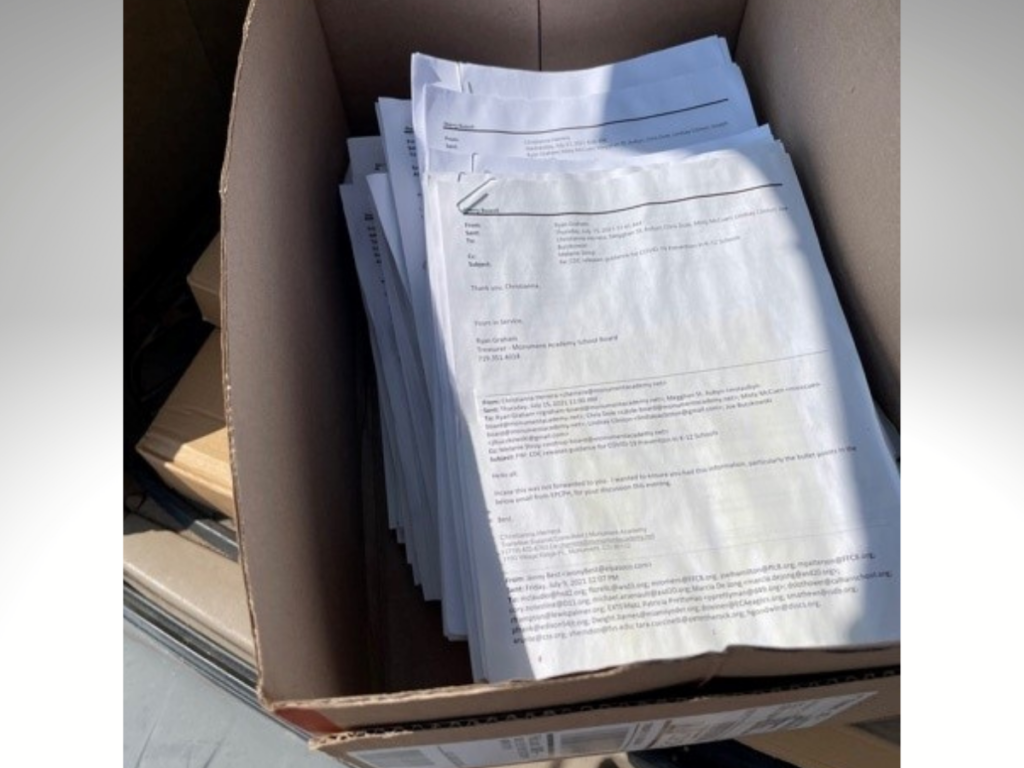

Because emails are created and maintained digitally, Bedingfield was surprised and annoyed when, three weeks later, Monument Academy had her pick up a box of paper records — with some of the 600 pages “warped as if wet and then dried” and others still damp and stuck together.

“Yes, sorry about that. The docs were delivered during a rainstorm. I noticed some stickiness as well,” the school’s attorney, Brad Miller, responded when Bedingfield asked why the records hadn’t been sent by email, as she’d wanted.

Bedingfield again requested digital copies of the records and a refund of at least some of the $134.32 she’d paid Monument Academy. She copied Lewis-Palmer School District officials on her correspondence with Miller, and she spoke about the school’s frustrating response to her request during the public comment period of a Monument Academy board meeting.

“I am shocked at the unprofessional conduct of Monument Academy, and no one can say that this is anything otherwise,” she told the board.

But the school and the district ignored her, Bedingfield said, until attorney Eric Maxfield filed a notice of her intent to sue the school’s board of directors.

“The Board, despite requests to counsel and directly at a public meeting, has failed to provide a declaration explaining the reasons it did not provide electronic records and instead provided rain soaked, damaged records,” Maxfield wrote to Miller on Sept. 14. “Such conduct violates CORA and meets the arbitrary and capricious standard.”

Bedingfield quickly received a searchable PDF of the records she requested — emails between Monument Academy board members and the school’s former chief operating officer — although she says most were duplicates. The school also refunded all her money, but she is still waiting to hear whether it will change elements of its CORA policy, as requested by Maxfield, that create other “unnecessary” barriers to public access.

The searchable PDF that Bedingfield eventually received is required under Senate Bill 17-040, which was meant to stop records custodians from providing requesters with paper copies of emails, spreadsheets and database exports rather than easy-to-analyze electronic files. The 2017 CORA amendment clearly states that public records stored in digital formats must be provided to a requester in a digital format, one that is searchable or sortable if the records are kept that way.

Another CORA provision, enacted in 2013, allows requesters to ask that records be sent to them by email once the records custodian receives payment or arranges to receive payment. Bedingfield did just that, but instead received the box of printouts.

“The Board has failed to transmit the records by email,” Maxfield noted in his letter, “has unreasonably required Ms. Bedingfield to travel to pick up the documents, and has provided damaged, wet documents that stuck together. The Board’s conduct is a failure to provide timely and full access to public records.”

Maxfield’s letter also demanded that the school properly cite CORA exceptions permitting it to withhold certain email exchanges deemed privileged. And he noted that a school official originally told Bedingfield she would be charged $35 an hour for four hours of research-and-retrieval time, even though the maximum allowable hourly rate under CORA is $33.58.

Maxfield and Bedingfield also are offering several suggestions for improving the school’s open records policy. Among them: An online payment platform; the delivery of requested records in a searchable, digital format; and the elimination of a rule that gives individual requesters just one free hour of research-and-retrieval time per month.

“There is no support in CORA for this approach,” Maxfield wrote, noting that the law merely says that records custodians may impose a charge “after the first hour of time has been expended.”

Bedingfield, whose three grandchildren attended Monument Academy, said she hopes her pushback will deter the school from responding to future records requests in a similar way. She noted that Miller is the attorney for several other charter schools and school districts.

“I have several things I’m working on, and this will help me,” Bedingfield told the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition. “He’ll be more responsive now. He is already.”

CFOIC has tried to contact Miller about Bedingfield’s records request, but he hasn’t yet responded.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.