By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

Major transparency legislation signed into law Friday by Gov. Jared Polis will let journalists and the public obtain records that show how law enforcement agencies in Colorado police themselves.

House Bill 19-1119, which went into effect immediately, introduces a statewide standard for access to records on completed internal affairs investigations conducted by police departments and sheriff’s offices. It upends a long-standing practice among most law enforcement agencies in Colorado to routinely reject requests for internal affairs files either with a blanket policy or a finding that disclosure would be “contrary to the public interest.”

The new law makes files related to specific incidents of an officer’s on-duty or in-uniform conduct “records of official action” that must be disclosed after certain required or discretionary redactions. It only covers investigations initiated after the bill’s effective date, and records custodians may first provide a requester with a summary before allowing access to a complete file.

“We want to make sure that the taxpaying citizens of Colorado have access to this information, especially when it’s their funding,” said Rep. James Coleman, D-Denver, who sponsored the bill in the legislature with Sen. Mike Foote, D-Lafayette. “And in our communities, we have people who want to build that trust and relationship with the law enforcement community. So for us, the importance of this bill is making sure we have that transparency.”

Foote called the measure a “win-win” for both communities and law enforcement agencies.

“The departments will be able to have more trust with the communities, and if there’s an internal investigation that shows that the complaint was meritless, then the community gets to know that,” he said. “I think the problem arises when somebody is denied access to records. They automatically assume that the records say something bad. We know that is not the case, and so now the public will be able to see that.”

The bill signing followed a two-year effort that was bolstered by the publication of a University of Denver Sturm College of Law study called “Access Denied.” Law professor Margaret Kwoka and her students documented how hard it is to obtain access to internal affairs files by requesting records from 43 agencies around the state. Only two showed any willingness to release IA files.

“Beyond demonstrating the sheer difficulty in accessing important public records, our study revealed another troubling finding,” Kwoka wrote in a recent letter to Polis that was signed by several DU law school faculty members. “The Colorado Supreme Court has ruled that agencies can only withhold internal affairs files after conducting a case-by-case balancing test, essentially testing the need for individual privacy or agency confidentiality against the public’s interest in the records. Yet, most agencies’ denials were across the board, without consideration of individual circumstances.”

The study concluded that these routine and widespread denials left Coloradans “largely in the dark with regard to allegations and investigations of police misconduct.”

Another letter to Polis came from groups that promoted HB 19-1119 and a similar bill that failed in 2018, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado, the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, the Colorado Press Association and the Colorado Broadcasters Association. Drafted by ACLU staff attorney Rebecca Wallace, the letter noted that certain provisions in HB 19-1119, such as mandatory redactions, accommodated the concerns of Colorado’s law enforcement community.

“We know that our state values government transparency, but for many years our law enforcement officers have been permitted to operate largely in secret, even when wearing a uniform and interacting with members of the public, even when a member of the public is badly injured or dies, and even when taxpayers have paid a significant sum to resolve legal claims against the officer and police department,” Wallace wrote.

She cited the case of Darsean Kelley, who was paid $110,000 by the city of Aurora to settle his claims against an officer who tased him in the back, even though he had complied with the officer’s orders to turn around and raise his hands. An internal investigation concluded that the officer’s actions were “reasonable, appropriate and within policy,” but the city refused to release the files. “The public has no opportunity to learn how the city could justify such a significant expenditure of taxpayer money and yet find no officer wrongdoing,” the letter says.

Fourteen other states – and now Colorado as well – allow public access to internal affairs files via statutory, constitutional or court-derived schemes. A 2019 study done for CFOIC by DU law student Brittany Garza showed that requesting internal affairs records in several of those other states “seemed almost as routine as requesting a traffic accident report, irrespective of prior criminal proceedings or press coverage.”

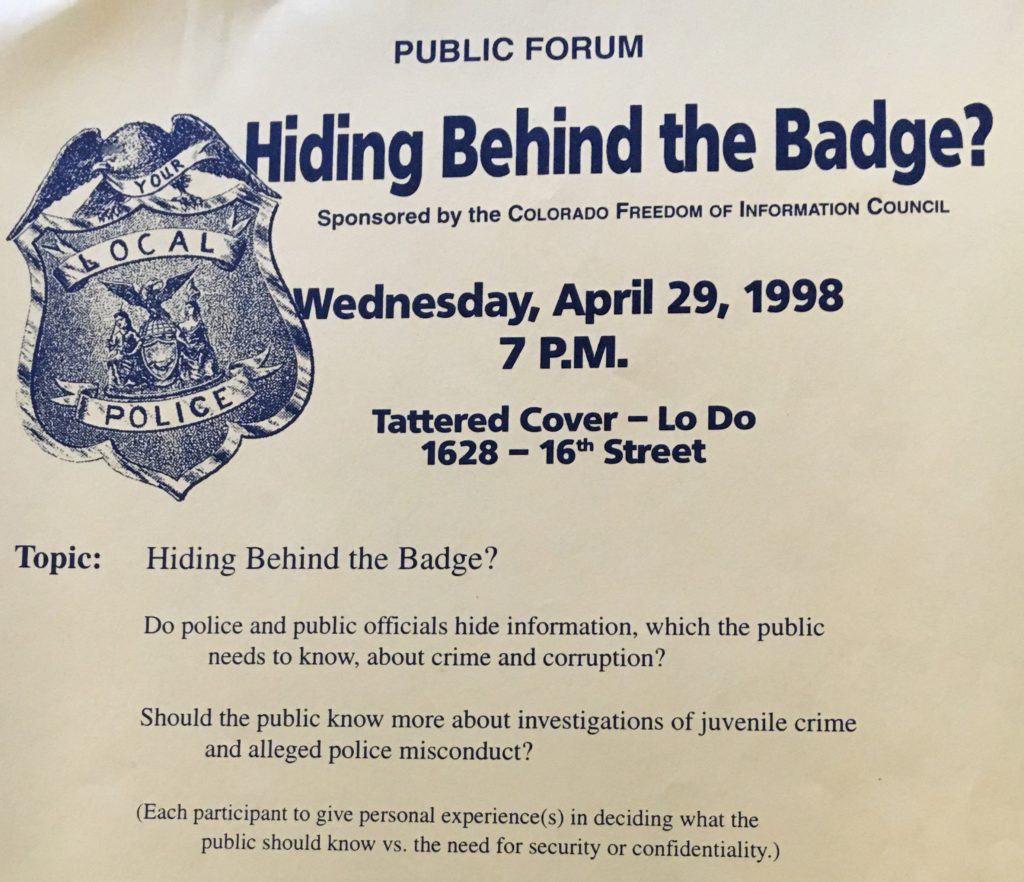

CFOIC has been calling attention to police secrecy for more than two decades. In 1998, the organization put on a public forum called “Hiding Behind the Badge?” at the Tattered Cover bookstore in lower downtown Denver.

For CFOIC President Steve Zansberg, law enforcement transparency has been “a personal mission.” As a media and First Amendment lawyer, he has worked on internal investigation records cases his entire legal career. One of his first, litigated with former CFOIC president (and current board member) Tom Kelley and ACLU legal director Mark Silverstein, led to the disclosure of internal investigation files concerning two Denver officers who manhandled a teenage suspect. Zansberg successfully litigated seven subsequent cases involving IA files and has written extensively about the issue.

HB 19-1119 is a “dramatic improvement” to Colorado’s open records laws, said Zansberg, who thanked the state lawmakers who championed it.

“The bill guarantees that going forward the public will be able to see for themselves how effectively police and sheriff’s departments police their own – at least when there are serious allegations of abuse or other misconduct by peace officers against civilians,” he said. “This transparency will contribute to the efficacy of that internal review process and will foster public confidence in the results.”

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.