By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

Coloradans fought for press freedom and freedom of information in 2025 in settings as small as the Eastern Plains town of Bennett and as big as the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C.

It remains to be seen whether some of these battles will be successful, including a First Amendment lawsuit brought against the Trump Administration for ordering federal funding cuts to National Public Radio and the Public Broadcasting Service because the president considers them to be “biased.”

Represented by media attorney and Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition president Steve Zansberg, Colorado Public Radio, Aspen Public Radio and KSUT Tribal Radio joined the federal court litigation, arguing that the executive order amounted to unlawful and unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination. “They’re standing up for all the other NPR member stations,” Zansberg recently told Corey Hutchins for his media newsletter.

A similar issue played out on a much, much smaller scale in Bennett where town trustees pulled the municipality’s display advertising from the weekly I-70 Scout and Eastern Colorado News because they didn’t like a story about an alleged sexual assault at a middle school. Because the board’s decision “was openly motivated by retaliation for The I-70 Scout’s editorial decision-making, the withdrawal of advertising was egregiously unconstitutional,” wrote attorney Rachael Johnson of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in a letter to the town.

Under a settlement agreement approved by the trustees earlier this month, the I-70 Scout will receive $15,000 from a municipal insurance pool and a three-year advertising contract, excluding legal notices, for $15,000 per year.

The town’s attorney called the settlement terms “a compromise, sort of balancing the town’s support of the First Amendment and also recognition of the board’s frustration with an article that was published by the paper.” I-70 Scout publisher Douglas Claussen said the trustees had no right to interfere with the operation of my newspaper or my freedom of speech, and this agreement attests to that fact, no matter how hard they try to mask it under the thin veil of morality.”

At the state Capitol this year, the public was saved from another legislative attempt to weaken the Colorado Open Records Act when Gov. Jared Polis vetoed Senate Bill 25-077, which would have given governments more time to respond to records requests, except for those submitted by a “newsperson” as defined by Colorado’s press shield law.

CFOIC opposed the bill. “By extending CORA response times to three weeks if governments claim that ‘extenuating circumstances’ apply — which happens frequently — SB 25-077 essentially gives records custodians an excuse to further delay providing public records within a reasonable period of time,” we wrote in a letter to the governor. “We know from the freedom-of-information hotline we’ve run for the past 12 years that government entities often miss the statutory deadlines, and there’s not much that Coloradans can do about it.”

Sen. Cathy Kipp, the Fort Collins Democrat who introduced SB 25-077, and a similar bill in 2024, has indicated she will try again in 2026 to lengthen CORA response deadlines. Kipp says this is necessary because records custodians are “essentially drowning in CORA requests.”

Also during the 2025 legislative session, CFOIC tried unsuccessfully to stop two bills that added significant CORA exemptions for public universities and Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Proponents of Senate Bill 25-038 said it was needed to protect ranchers from harassment when gray wolves kill their livestock, although the bill grants confidentiality to all claimants under Colorado’s wildlife damage compensation program. House Bill 25-1041, also signed into law by the governor, makes name, image and likeness (NIL) contracts between public universities and student athletes confidential.

In committee testimony CFOIC board member Eric Maxfield said that “concealing NIL records from the public disserves the interests of every stakeholder — the public, the athletes and college sports itself — in making sure that competition is fair, honest and passes the test of legitimacy, and that athletes have equitable earning opportunities befitting their level of accomplishment.”

CFOIC was successful in helping to persuade the executive committee of Legislative Council to test video livestreaming of committee meetings (Colorado was the only state that didn’t provide at least some video coverage of legislative committees). Legislative leaders still have not decided whether to spend $70,000 to keep the committee room cameras rolling for the 2026 session of the General Assembly, but they are set to take up the proposal on Dec. 31.

Here are other highlights and lowlights of 2025 featured on CFOIC’s blog and news feed:

A private judicial system. CFOIC asked a “private” judge to open the case file — with only “truly sensitive” information redacted — in a divorce being litigated outside of public view in a special Colorado judicial system described by The Denver Gazette as mostly available only to “the rich, famous and well-to-do.”

“This is not arbitration. This is not mediation. We are sitting in the district court … and every case litigated in this court is presumptively open,” Zansberg argued during an October hearing. Former Denver District Court Judge William Meyer of the Judicial Arbiter Group hasn’t yet announced his decision.

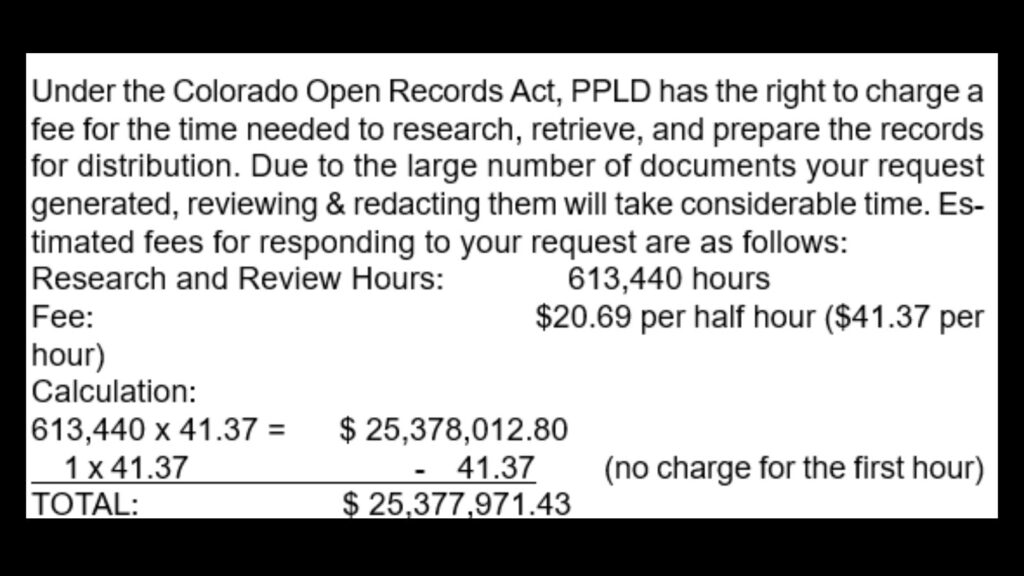

A $25.4 million CORA request. Lisa Bigelow later realized she could have done more to narrow the CORA request she submitted in March to the Pikes Peak Library District. Even so, she couldn’t believe it when the records custodian quoted her $25,377,971.43, claiming it would take the district 613,440 hours to “research, retrieve, and prepare” the documents she wanted. It could have been even more expensive — the custodian subtracted $41.37 because CORA requires the first hour of research and retrieval to be free.

Inmate awarded $13,650. In February, a Jefferson County District Court judge ordered the Colorado Office of the State Public Defender to pay prison inmate Eric St. George $13,650 — a $25-a-day penalty for 546 days — for its “arbitrary and capricious” denial of his Colorado Criminal Justice Records Act request for a policy document. In its appeal, the public defender’s office says its records are subject to the judicial branch’s records rules, not the CCJRA.

Signal use by mayor’s office. In March, CBS News Colorado reported that Denver Mayor Mike Johnston and several of his top advisers communicated about the city’s migrant crisis using Signal, the encrypted messaging app, which automatically deleted their initial conversations. The next month, Johnston’s spokesperson acknowledged that office personnel had been using Signal to monitor news stories and that comments and conversations had been automatically deleted.

“Seems like a pretty plain, straightforward, deliberate effort to evade transparency,” Zansberg told reporter Brian Maass.

Notarized records requests. Earlier this month, an attorney for 9NEWS and Colorado Public Radio challenged a Weld County Sheriff’s Office requirement that records request forms be notarized, writing in a letter that it “creates an arbitrary and unreasonable hurdle” and “does not serve any legitimate government interest.” Before pursuing a court order, CFOIC board member Madison Schaefer of the Killmer Lane law firm gave the sheriff’s office until Jan. 9 to “voluntarily cease” what her letter calls “an erroneous policy which contravenes the statutory intent and purpose” of the CCJRA.

Cure doctrine. In September, the Colorado Supreme Court affirmed a judicially created doctrine that lets public bodies “cure” violations of the Colorado Open Meetings Law at subsequent meetings that do not merely rubber-stamp earlier decisions. The case concerned the Woodland Park school board, which in January 2022 discussed a memorandum of understanding with Merit Academy charter school under a “BOARD HOUSEKEEPING” agenda item.

A newspaper is a citizen. The Aurora Sentinel is a “citizen” entitled to recover attorney fees and court costs for prevailing in an open meetings lawsuit against the Aurora City Council, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in October. The justices did not, however, directly address whether the newspaper should get the full audio recording of a March 2022 executive session in which councilmembers ended censure proceedings against then-Councilmember Danielle Jurinsky for comments she made on a radio talk show about Aurora’s then-police chief and deputy chief. The case is now back in Arapahoe County District Court.

No lawsuits over delayed records. In January, the Colorado Court of Appeals ruled against a man who sued the First Judicial District for delaying its response to his records request. P.A.I.R.R. 2, which governs the disclosure of judicial branch administrative records, “provides no cause of action when all responsive records have been made available for inspection, even if the production of those records was delayed,” the appellate court decided. There is no comparable high court ruling about CORA delays, but the language in both records rules is similar regarding response times and the ability to sue in district court over a denial of records.

Executive session oopsie. The Summit School District unintentionally posted the recording of a November executive session online, angering union members who were discussed during the closed-door meeting. The district claimed the session complied with the open meetings law, but the recording revealed that board members talked about unauthorized topics beyond the stated purpose — the superintendent’s performance review.

Water consumption records. Business Insider in January successfully sued the Denver Water Board and Colorado Springs Utilities to win the disclosure of water consumption records for large data processing centers. Both claimed the documents couldn’t be disclosed under a CORA exemption that protects the “personal financial information” of public utility users.

DougCo commissioner luncheons. Three residents of Douglas County are appealing a judge’s May ruling that the open meetings law did not apply to 11 “advance planning meetings” and three “elected officials” luncheons during which the county commissioners met outside of public view. “The District Court’s legal conclusion was erroneous: numerous topics of the Board’s ‘public business’ — meaning matters that bore a meaningful connection to the policy-making functions of the Board — were discussed in the course of those meetings,” a Court of Appeals brief says.

Aurora PD bodycam footage. An Arapahoe County District Court judge in June ordered Aurora to release all unedited body-worn camera footage of police shooting and killing Kilyn Lewis, finding that the city denied 9NEWS’ requests for the video in violation of Colorado’s Law Enforcement Integrity Act.

Lakewood PD bodycam footage. In July, the Court of Appeals ruled that Colorado’s Children’s Code does not prohibit the public disclosure of blurred body-worn camera footage of Lakewood police shooting and killing a 17-year-old robbery suspect in 2023. The appellate judges rejected Lakewood’s argument that the statute which protects the confidentiality of juvenile records trumps the footage-release provisions in the Law Enforcement Integrity Act.

Boulder PD bodycam footage. CFOIC and the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado in July asked the Court of Appeals to affirm that the Law Enforcement Integrity Act does not permit agencies to charge requesters hundreds or thousands of dollars for body-worn camera footage showing possible misconduct by police officers. In the underlying case, a Boulder County District Court judge ruled that Boulder police cannot make Yellow Scene Magazine and Jeannette Orozco pay the city $2,857.50 to obtain video of police shooting and killing Orozco’s 51-year-old mother, Jeanette Alatorre, in 2023.

Book ban. The Elizabeth School District in May returned 19 banned books to its school library shelves following a judge’s order in a lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado. In late November, a former middle school administrator sued the district, alleging she was fired after objecting to the book removals.

Full and timely notice. An Elbert County District Court judge ruled in April that the Elizabeth School District failed to give the public proper notice of a 2023 board meeting about a resolution that opposed mask and vaccine mandates. “The public has a right to know what our elected officials are doing with our tax dollars so that we can participate in the process if we choose to do so,” said Jessica Capsel, the plaintiff in the case.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on X and Bluesky. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.