By Sandra Fish

CFOIC Contributor

Trying to get to the bottom of a small town’s faltering finances. Fishing expeditions prompted by an election-denying social-media post. Information about one of the most-watched college football programs in the nation. State legislators’ records about UFOs.

Using the Colorado Open Records Act, originally created by the Colorado legislature in 1968, citizens, reporters, businesses and organizations sought a range of information from Colorado governments in 2024.

The Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition examined more than 12,000 CORA requests made last year to the governor, treasurer, attorney general, secretary of state and legislature, along with selected other state agencies, county clerks, school districts and cities. That’s likely only a fraction of the requests made to all local, county and state government bodies.

Among the findings:

- Most requesters are individuals or businesses and include lawyers, private investigators and nonprofit think tanks. About 6% of requests came from journalists.

- Governments denied or partially denied about 2% of requests in which information about responses was evident. Denials often were made because information about individuals or companies was considered confidential.

- Nearly 18% of requests with response information either had no records available or were referred to other agencies.

But responses from the selected governments were inconsistent and often incomplete, making a detailed analysis difficult:

- Some agencies provided digital logs with details about the dates of the requests and responses, the people making requests, their affiliations, if any, and the nature of their requests.

- Some logs, however, didn’t include key information, such as what the requesters asked for, whether fees were charged or when the response was delivered.

- Some agencies — including Gov. Jared Polis’ office and the Mesa County clerk — provided only PDFs of requests and responses, which had to be manually entered into a spreadsheet.

- Some agencies initially refused to provide requesters’ names, claiming that “personally identifiable information” is exempt because of a 2021 law. But that law only exempts requesters who are inquiring about immigration matters.

- Seven agencies redacted names of requesters in 140 instances, claiming they were confidential under other laws.

Celebrating transparency laws that are under attack

This week is Sunshine Week, a national celebration of government transparency laws. Some state’s open records laws date to the 1800s, and they provide the ability for people to get information about government and how it works — or doesn’t, said David Cuillier, director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida. “We have so much research that shows that public record laws lower corruption. They hold government accountable. They save us tax dollars. They make government more efficient.”

But governments are becoming less responsive, the Brechner Project has found.

“Our data show that secrecy is increasing at all levels of government,” Cuillier said. “Ten years ago, if you asked for a public record in the U.S, you’d get it, on average, about half the time. Now it’s down to 13% of the time, and it’s a steady line down.”

The CFOIC analysis comes at a time when open records laws are being scrutinized by lawmakers and politicians in Colorado and around the nation. Some states have enacted laws to label frequent requesters as “vexatious” and other states are considering such laws. Colorado lawmakers removed such a provision from an open records bill last year.

“It’s really just a deluge of secrecy, exemptions and attempts to help local government from what they say are ‘vexatious’ requests and creating new laws that are framed as making government more transparent, but in reality, just make it worse,” Cuillier said.

This session in Colorado, lawmakers have passed one bill that would make university payments to student athletes confidential and are considering another that would extend deadlines to respond to CORA requests. A third measure that failed would have capped fees to fulfill those requests.

“State legislators these days are much more inclined to ease the burden on government records custodians than they are to remove barriers to access for journalists and the public,” said Jeff Roberts, CFOIC’s executive director. “We’ve tried for years to get them to reevaluate the formula for setting CORA fees, which have gotten out of control, but there’s very little interest in doing that.”

Most requests are mundane

Though journalists may not be the most frequent users of open records laws, the stories they produce get the most attention.

But everyday people also use public records to impact government.

Journalist Miranda Spivack’s book “Backroom Deals in our Backyards” highlights local people who used open records to uncover problems in their communities, from dirty drinking water to traffic accidents. There’s even a brief mention of Erie residents who were denied information about fracking chemicals using trade secrets exemptions.

“In five different communities that I used as the examples, people had a very hard time getting information,” Spivack said. “There was no sort of rhyme or reason to it … In many cases, records still aren’t digitized, especially in small communities.”

Many of the requests reviewed by CFOIC were more mundane, with businesses and individuals often seeking routine information.

More than 2,700 went to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, with more than half of those directed at the Hazardous Materials and Waste Management Division. Most were related to permit information.

The Colorado Department of Revenue responded to nearly 1,400 requests, mostly regarding professional licenses and real estate. The city of Lakewood responded to 1,100 requests, the city of Gunnison responded to 86.

Many of Lakewood’s requests dealt with building permits. Gunnison got three requests about the city’s bidding process for holiday lights.

Polis’ office received only 69 requests. It provided 177 pages of emails that CFOIC logged in a spreadsheet after the office said it didn’t have any sort of system to track CORA requests.

Redacted records

The Colorado Department of Human Services accounted for nearly half of the 140 instances where the names of requesters were redacted because of confidentiality requirements. The agency supervises child protection as well as adult, aging and disability services.

Poudre School District redacted requester names in 31 instances, with one person making 22 of those requests. The district said it received 239 requests in 2024, but provided logs in PDF format for only 210 requests.

Requests to Poudre schools in 2023 appear to have spurred the 2024 attempt to label some requesters “vexatious.” While the language was ultimately removed, there are still some in government who would like to see restrictions on people they view as troublesome requesters.

Earlier this year, Durango School District R-9 listed limits on “extreme or gratuitous” records requests as one of its legislative priorities, The Durango Herald reported. The district received 18 CORA requests in 2024, with the name of the requester redacted in 10 instances.

Three of the Durango requests centered on diversity, equity and inclusion policies, while two asked for information about a former teacher charged with enticing a minor and other crimes. The La Plata County GOP tried to link DEI policies with the former teacher, according to The Herald.

Cuillier said Connecticut and Utah both have laws that prevent people deemed “vexatious” from submitting open records requests for a year. But both have seen limited use.

Spivack’s book shows how some people become “accidental activists” when “something’s happening in their community and they want to find out about it.” Her reporting also illustrates how difficult — and costly — getting information from government can be.

“It’s not a priority because it isn’t funded,” she said. “And some of it, obviously, is deliberate.”

Spivack offered this advice for those just learning about the process.

“Go to City Hall in person,” she said. “Find the people who you will have to write a request to and talk to them, find out what records they have … Befriend them. Because actually, a lot of these people would like to help you, even if their bosses might not like to help you.”

CFOIC sought out the stories behind several of the requests.

A small town budget, a federal grant and a CBI investigation

When Paul Sammataro bought a home outside the town of Aguilar in Las Animas County, he wanted to get involved in the community.

“We started out volunteering and donating and doing different things,” he said.

When Sammataro heard rumors about possible financial mismanagement in the town, he started looking into its finances. The town hadn’t conducted an audit since 2018, and it had received $5.8 million from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2021 for a water project.

Sammataro and freelance journalist Ruth Stodghill filed most of the 18 open records requests with state agencies about Aguilar’s finances last year. Both said they had more success getting information from state and even federal officials than from the town.

“The town has been very resistant to giving me information,” said Stodghill, who writes for the local World Journal newspaper.. “When there’s more than one entity involved, and I can go to those other entities to request the information, that has been helpful.”

Last summer, Stodghill reported that the town’s general fund dried up and checks were bouncing, in part because of complications with the water project. The town clerk was placed on leave. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation began looking into town finances, which could take up to two years.

Stodghill said information she received from a CORA to the state auditor revealed the town’s audit issues, as well as problems in audits dating to 2016.

Deputy Town Clerk Sara Porras said CORA requests sometimes take time to fulfill. And she said the city is catching up on the audits that weren’t done in the past.

Public records are essential for citizens to learn how the government is spending taxpayer money and serving the public, Sammataro said. “The government is for the people, and if you’re for the people, you have to be transparent. You have to allow the people to make requests for government public documents.”

For Sammataro, such activity was a first.

“I have never been to a city council meeting in my life — until I moved to Aguilar.”

Should payments to student athletes be public?

The University of Colorado Boulder received nearly 300 public records requests in 2024, with one-third concerning sports, associate CU general counsel Katie Gleason told lawmakers recently. A Washington Post investigative sports reporter paid $1,159 for one request. Others came from ESPN, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times and Sportico.

CU’s 2022 hiring of football coach Deion Sanders put a national spotlight on the program. The former All-American cornerback and two-time Super Bowl champion brought his sons and other players with lavish endorsement deals to the Boulder campus.

With college players allowed to earn money for use of their names, images and likenesses (NIL), money has poured into athletics. Up to now, players have often received deals through endorsements with companies. But beginning in July, large conference universities will be able to pay students directly.

Lawmakers last week passed a bill to exempt specific payments to athletes from public view. University officials cited the mental health of athletes at a House committee hearing as a reason to keep the payments from the public. CFOIC and other open government advocates objected to the bill.

Colorado Press Association CEO Tim Regan-Porter told lawmakers the provision ultimately protects universities more than anyone.

“It protects the system itself from accountability, from scrutiny, from ensuring fairness,” he said. “What about the hundreds of other athletes whose NIL deals might not be fair or equitable? What about the potential manipulation and favoritism that inevitably creeps into unregulated, hidden systems?”

The CU Boulder campus received plenty of CORA requests beyond sports. Olivia Doak, the Daily Camera’s higher education reporter, filed 56 with CU Boulder and four others with the CU system and the Colorado Department of Higher Education. Some were routine — she often files requests about other CORA requests and for salary listings, for instance.

Others are spurred by tips and lead to news stories. For instance, when she heard about unsafe working conditions at Macky Auditorium, she confirmed the tip after requesting public records. CORA requests also led to stories about a CU finance professor who contributed to Project 2025 and an investigation that concluded a dean retaliated against a professor.

“I use public records in my reporting all the time, and it’s just so important,” Doak said. “Even little things that I can request that kind of supplement a story are just so critical.”

A flurry of identical requests to a county clerk and the secretary of state

Shortly after former Mesa County Clerk Tina Peters was sentenced to nine years in prison for breaching the county’s election system in 2021, a social media post suggested an open records request be sent to Mesa County and the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office.

On Oct. 3 and the following day, the secretary of state and Mesa County clerk each received 17 requests patterned on the post. The requests began by asking for court documents including “transcripts, filings, motions, orders, and judgments from the legal proceedings against Tina Peters from April 2021 to the present,” but also requested communications, investigative records, sentencing information and more.

Both offices pointed out that they didn’t have the court documents. And the secretary of state’s office noted that after five hours, it had compiled 30,000 pages of documents that would need to be reviewed “to conform with all legal withholding requirements.” Mesa County sent a similar response.

The cost? Nearly $48,000 for the state documents and $1,500 for the Mesa County documents.

None of the requesters paid the money, most having said they were willing to pay up to $17.

In 2024, former Republican gubernatorial candidate Heidi Ganahl paid Douglas County $12,162 to examine select ballots from the 2022 general election, which she lost to Polis by 19 percentage points. She paid another $320 for signature verification information and Dropbox video from the 2022 election.

Originally, Ganahl asked to inspect all 2022 ballots and the county quoted a fee of nearly $213,000.

Many requests to county clerks in Mesa, Boulder, El Paso, Denver and Douglas counties reviewed by CFOIC dealt with people questioning election procedures. Since President Donald Trump contested the outcome of the 2020 election, followers including Peters and Ganahl have continued to search for evidence supporting their false claims.

Matt Crane, executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association, said such requests continue to increase work levels for clerks, despite a 2024 law giving them more time to respond during election periods.

“We saw a very small movement on the left use some of the same tactics after the (2024) election when President Trump won, but right now, it is predominantly on the right,” Crane said. “The people who are encouraging (others) to do this know this will slow down election offices, hinder election offices.”

Lawmakers get requests about emails

About 28% of the 246 CORA requests to the state legislature came from journalists.

But Rep. Ken DeGraaf, R-Colorado Springs, was the top requester with 20 CORAs sent to Democratic lawmakers about climate policy.

Many of the requests sought correspondence concerning various controversies such as:

- Former Republican Leader Mike Lynch being on probation for DUI. He ultimately resigned his leadership post and lost his bid for the GOP nomination in the 4th Congressional District.

- Allegations that former state Sen. Sonya Jaquez Lewis, D-Lafayette, treated her aides unfairly. She resigned last month as an ethics investigation was wrapping up.

- The failure of former state Rep. Elisabeth Epps, D-Denver, to attend House floor work in person until more than a third of the way through the session. She lost her Democratic primary bid.

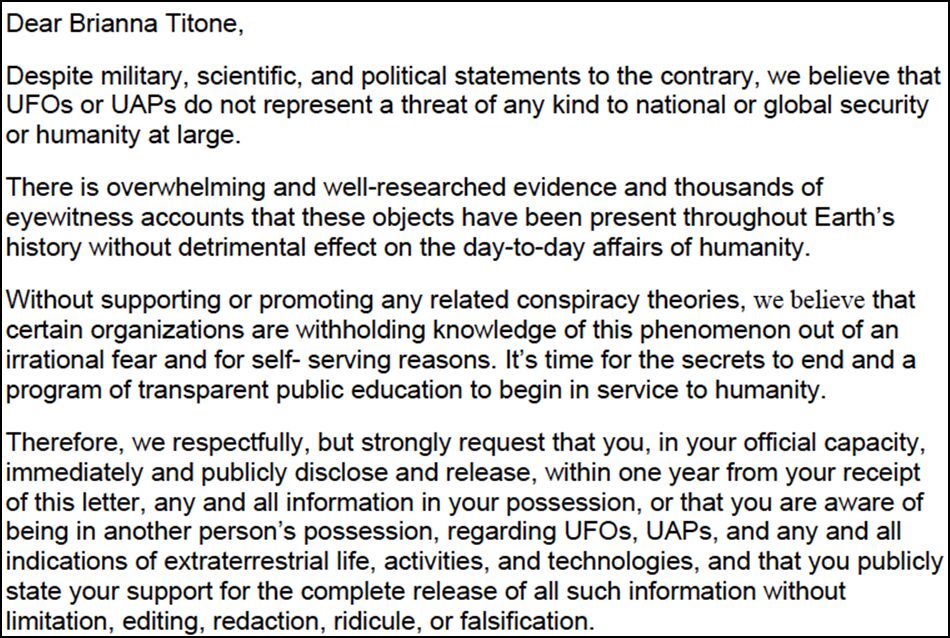

Seven requests to lawmakers were about UFOs.

“I am reaching out to you, as a dedicated public servant, to request your advocacy in advancing government efforts towards greater transparency regarding UFO/UAP (Unidentified Aerial Phenomena) encounters,” wrote an Aurora resident.

Rep. Sheila Lieder, D-Littleton, was the only lawmaker who responded with any documents to that request. She provided emailed newsletters, mostly from the Aerospace States Association.

Rep. Brianna Titone, D-Arvada, received similar requests but told CFOIC she had no responsive documents.

“I am not harboring any information about the existence of UFOs,” Titone said. “I am curious about this thing as much as anybody else is. But I do not have any answers.”

Titone stressed that CORA requests are absolutely essential for government transparency.

“I mean, you know, the truth is out there.”

Sandra Fish recently retired as a data journalist and politics reporter for The Colorado Sun.

Reuben Schafir of The Durango Herald, Suzie Glassman of Colorado Community Media, Bella Biondini of The Gunnison Country Times and Lia Salvatierra of the Ouray Plaindealer also collected data for this story, which Fish analyzed for CFOIC.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on X or BlueSky. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.