By Sandra Fish

FAIRPLAY – Imagine that Stan and Kyle of “South Park” cartoon fame want precinct-level election results.

They call the county clerk and find out the results aren’t kept electronically – they’re in large ledger books, written by hand. To see them, Stan and Kyle are told, they must come into the office.

So they make the trip, figuring they’ll take photos of the pages with their smartphones and then convert the images to PDFs. (It’s 2016 and those “South Park” kids are modern types, right?)

Sandra Fish

But when Stan and Kyle get to the county clerk’s office, there’s a sign that says something like “No phones or laptops allowed.” No such devices are allowed in the room with the ledger books nor anywhere else in the office.

Stan and Kyle ask why. “It’s state law,” they’re told. “Are you sure about that?” they ask.

They also ask if they could get copies of the pages scanned and emailed from the clerk’s modern copy machine. If they want emailed copies, they’re told, it will cost $2 a page vs. $1.25 a page for paper copies ($1.25 a page because ledger books are non-standard size).

So they’ve got to identify the pages they want copied, fill out a form, wait three days, call again, pay by credit card (with an undisclosed fee tacked on), wait for their public records to arrive in the mail, find a copy machine to scan the copies and then email the copies to themselves.

Sound like a goofy cartoon? It actually happened.

One early morning in June my 18-year-old nephew and I drove to the Park County Clerk and Recorder’s office in Fairplay, the town that “South Park” was modeled on.

I was on an errand for Open Elections, a group that’s assembling a free, comprehensive source of U.S. election results since 2000 down to the precinct level.

And when I got out my iPhone, suggesting it would save everyone time and money for me to take photos of the handwritten ledger pages, I was told that wouldn’t be allowed. I noted the signs prohibiting phones or laptop computers in the area.

Asked about the camera/computer ban, Clerk and Recorder Debra Green said she understood it was state law, based on information from the Colorado County Clerks Association.

Because I wanted the records, I agreed to fill out the form, etc. and pay $14.54 for copies and postage.

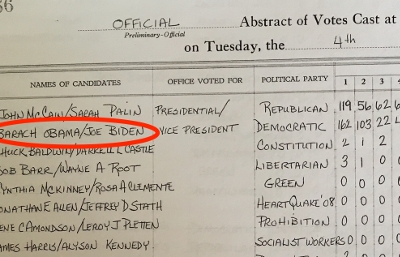

From Park County’s ledger of votes cast in the 2008 general election.

But once the records arrived in the mail, I made some phone calls.

Pam Anderson, executive director of the clerks association, said she had no idea what Green was referring to.

“I don’t recall any explicit guidance or instructions like that. I don’t see it as much different than taking notes,” Anderson said of using electronic devices to record the handwritten information.

Media attorney Steve Zansberg, president of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, said he knows of no law prohibiting citizens (or journalists – we’re citizens, too) from using phones to take photos of public records.

“You can’t take notes using a laptop?” he asked. “That makes no sense at all.”

So I called Green back to ask about the prohibitions.

She’d apparently received a call from Anderson and revised where the camera/computer ban originated.

“I would say from my previous clerk,” Green said. “Those are our documents and if you want copies we’ll make them. The previous clerk posted that and I’ve just followed through with that.”

Green said she would be reconsidering the prohibition.

But Park County, she added, would continue to track precinct-level election results by hand in ledger books. The office started a new book in 2015. Green said the results couldn’t be transferred to the office’s computers from election equipment, even though it is digitized.

“Every election is in there, and it’s all handwritten,” Green said.

Meanwhile, my nephew Charlie Fish, a recent high school graduate, got a bit of a civics lesson on this trip (in addition to listening to an interview with Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson in the car). As a digital native – maybe digital immersive is a better term – he was not impressed.

“They need to get more modern, start living in the 21st century,” Charlie said. “It was just so ridiculous on so many levels. It’s public data. It should not be that complicated.”

I’ve spent the last few evenings digitizing Park County’s handwritten results by typing them into a spreadsheet (and correcting the spelling of a certain presidential candidate’s first name in the process).

After that’s done, Park County officials – and anyone else – will be able to find the files here, where the Open Elections project is storing Colorado files until they’re ready to be processed.

Sandra Fish is a data journalist for New Mexico in Depth and president of the Journalism & Women Symposium. Follow her on Twitter @fishnette.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.