By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

When state lawmakers took up collateral-consequences legislation this past session, creating additional opportunities for the sealing of lower-level criminal records, the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition wrote about the bill’s potential negative effects on public-service news reporting.

In testimony, journalists worried that closing additional records will make it harder to identify systemic problems in the criminal justice system and hold public officials accountable for bad behavior. But they also expressed sympathy for giving people second chances. Not discussed in that House committee hearing: Some news organizations in Colorado are acting on that sentiment, establishing policies that let story subjects formally ask that their names be removed from long-ago articles that live online indefinitely.

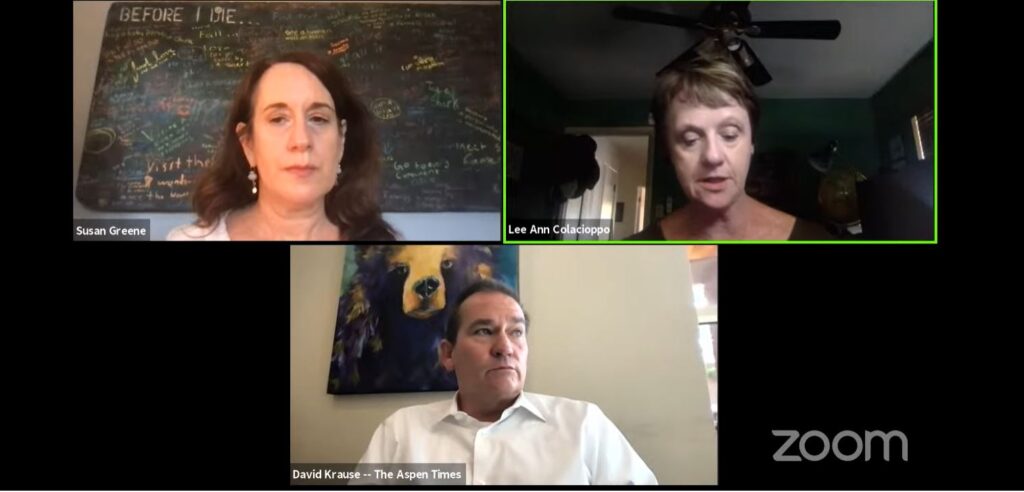

Such policies are part of what’s being called the “right to be forgotten” or “right to erasure” movement. “This is the idea that people should possess some ability to make sure that false or damaging information about them doesn’t linger forever online,” making it harder for them to get jobs, find housing or even get a date, said journalist Susan Greene during a Zoom panel discussion earlier this week. For news organizations, led in the United States by The Plain Dealer newspaper in Cleveland and its sister publication cleveland.com, it means “trying to strike a balance between the rights of the subjects and the public interest in the information about those subjects.”

Greene, who reports for the Colorado News Collaborative (COLab), moderated the panel, which included Denver Post Editor Lee Ann Colacioppo and Aspen Times Editor David Krause. Both The Post and The Times recently wrote right-to-be-forgotten policies, with The Post also establishing new guidelines for its breaking news reporters. Colacioppo said those guidelines, in part, caution reporters that “every time you name someone who was arrested, that’s a case we must follow and ultimately report the outcome. Be judicious in including arrestees’ names if it’s not a serious crime. For example, with the George Floyd protests, we did not publish long lists of protesters who had been arrested.”

The breaking-news policy “bubbled up out of the staff and the people who have been reporting those stories,” Colacioppo said. “We sought to make better choices, smarter choices, do a better job of really representing our community in a fair and accurate way.”

In April, The Aspen Times published an editorial explaining its right-to-be-forgotten policy and it posted a form — also used by other newspapers in the Swift Communications chain — that people can use to request that their names be removed from stories. To qualify for consideration, the story can’t involve a public official and must pertain to a non-violent, victimless crime. The person submitting the request is asked to upload court documents showing that their record was expunged.

“These stories were true and accurate at the time, so that’s not the issue,” Krause said. “The issue for us on a lot of these is, at what point should the person be responsible for a 12-year-old story that we wrote that, frankly, we probably wouldn’t write now?” These stories, he added, often concerned a visitor “who probably went a little too hard and treated Aspen like Vegas and didn’t think it would just stay here in Aspen. Those are a lot of them.”

For The Post, expungement or sealing does not necessarily lead to changing a story, Colacioppo said. She cited the recent example of a person who pleaded guilty to a child sex-trafficking crime. “In that case, due to the nature of that crime, there are reasons some of these things should still remain in the public view.”

Krause said The Times gets four to 10 requests per month. The Post, Colacioppo said, might get four or five in a week and zero in some weeks, but it hasn’t yet published an online request form. She said many of the requests she evaluates don’t involve crime stories.

“There are people who are embarrassed by something that was written about them or just kind of regret ever having talked to us to begin with,” Colacioppo said, “like when we wrote about someone who was homeless and now some amount of time has passed. Or they talk to us about a mental illness issue or maybe a domestic violence.”

Both Colacioppo and Krause said they remain wary of legislative efforts to seal criminal records, especially for more serious crimes.

“These are, at their heart, public records and should remain so,” Colacioppo said. “When you start shielding things like that … you really do lose the opportunity to find out that this person who is running for office once did X, Y and Z. Or take, for example, the police officer who was arrested yesterday in Aurora. He had a conviction in his past and that was quite relevant to the story.”

Sealing public records, she said, also makes it difficult for news organizations to look at criminal-justice trends such as whether rape allegations are being investigated evenly across the state. “You start hiding these records, I think you do a great disservice to everybody’s ability to really understand important trends and issues of the state.”

COLab presented Wednesday’s Zoom panel discussion along with CFOIC, the Colorado Press Association, the Colorado Media Project and the Denver Press Club. You can watch it here.

Read more about how Colorado newsrooms are rethinking their crime reporting in this column by Corey Hutchins, who writes about the news media and teaches journalism at Colorado College.

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.