By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

Despite a 2019 state statute requiring the public disclosure of police internal affairs files in Colorado, the town of Ouray for months released only heavily blacked-out copies of records concerning excessive-force allegations against officers.

It took the involvement of an attorney, Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition president Steve Zansberg, for the Ouray County Plaindealer to finally obtain less-redacted documents that could be understood when read.

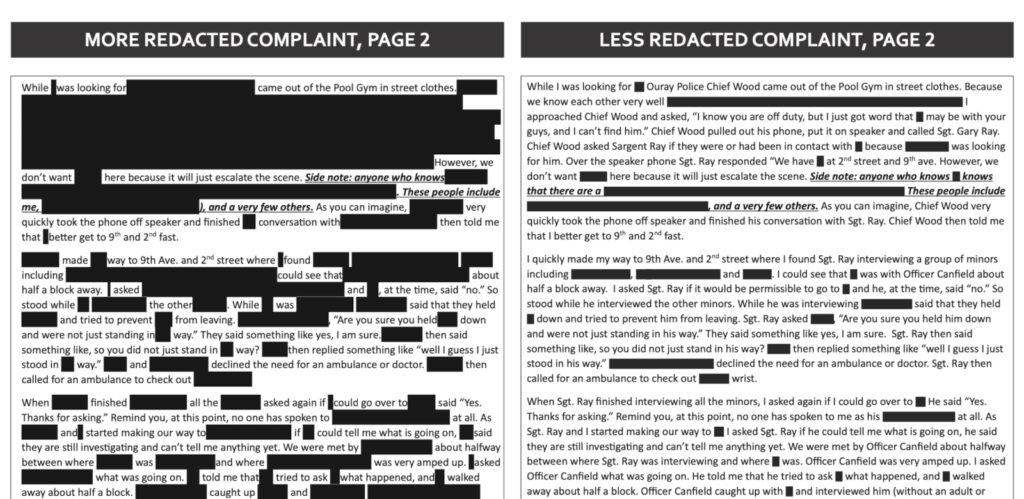

The dispute began last spring when the newspaper asked for records about allegations Ouray police had acted improperly when arresting a 14-year-old boy in June 2023. The city provided a 10-page citizen complaint and a nine-page internal investigation report showing the department had been cleared of misconduct, but the “substance and details” of what occurred remained secret because of the extensive redactions, the Plaindealer reported.

Not only were the narratives nearly impossible to follow, but the names of the officers involved in the incident were covered over as well.

City officials claimed the redactions were necessary because the use-of-force complaint and investigative report involved a juvenile whose criminal record had been expunged after he completed a diversion program. They cited Colorado’s expungement statute, C.R.S. § 19-1-306, which makes confidential “basic identification information on the juvenile and a list of any state and local agencies and officials having contact with the juvenile, as they appear in the records.”

But Plaindealer co-publisher Erin McIntyre hadn’t requested records about the juvenile’s crime, only records about the police officers’ conduct. When she reached out to CFOIC, we pointed out that the 2019 statute on law enforcement internal affairs files requires the redaction of “identifying information related to a juvenile,” but not information about the accused officers.

The statute opens records of completed internal affairs investigations that examine “the in-uniform or on-duty conduct of a peace officer … related to an incident of alleged misconduct involving a member of the public.” An entire investigation file must be made available upon request, including witness interviews, video and audio recordings, transcripts, documentary evidence, investigative notes and a final departmental decision.

Under the law, certain information may be redacted from disclosed internal affairs files and certain other information must be redacted. Aside from “any identifying information related to a juvenile,” the must-redact list includes: personal identifying information such as Social Security numbers, driver’s license numbers and passport numbers; information that identifies confidential informants, witnesses or victims; and a law enforcement officer’s home address, personal phone number and personal email address.

Otherwise, the files of completed internal affairs files “must be disclosed upon request,” Zansberg wrote in a May 30 letter to Ouray City Administrator Silas Clarke. “The excessive redaction of these two documents (withholding not only the names of all city employees but also the date of the incident in question, as well as entire sentences of text) cannot possibly be justified by § 24-72-303(4)(b)(VI) C.R.S., which requires records custodians to withhold only ‘Any identifying information related to a juvenile.’”

The fact that the boy’s juvenile delinquency records have been expunged “has absolutely no bearing on the non-juvenile delinquency records that Ms. McIntyre requested and you have provided her,” he added.

Well before the enactment of the 2019 law, Zansberg also noted, the Colorado Supreme Court in 2008 ruled that when determining how much of a completed internal affairs report should be disclosed, a records custodian should “redact sparingly to promote … the preference for public disclosure” in the Colorado Criminal Justice Records Act. Redaction “is an effective tool to provide the public with as much information as possible, while still protecting privacy interests when deemed necessary,” the justices also wrote.

Denver attorney Nick Poppe, hired as outside counsel for Ouray, replied to Zansberg on June 11, maintaining that the juvenile expungement statute “commands that all ‘records’ are not open to the public following an expungement.”

“[T]here is nothing in the CCJRA that warrants ignoring other provisions of state law that preclude disclosure of certain records,” Poppe added. “… In other words, the statute allowing for the release of certain internal affairs records does not trump other statutes that protect the legitimate privacy interests of Colorado citizens.”

But on June 21, the city finally agreed to give the Plaindealer much-less-redacted versions of the documents. If the records qualified as juvenile delinquency records, Zansberg had told Poppe, they should have been withheld in their entirety. Providing the newspaper with less-redacted versions, he had written in his May 30 letter, “will obviate the need for us to ask a judge to determine” whether the “scope and extent” of the redactions was proper.

Ouray released the investigative report in early July but waited until later in the month to provide an “intelligible” version of the complaint.

In a July 31 column, McIntyre decried Ouray’s lack of transparency.

“These redactions were excessive. They were unnecessary. They weren’t meant to protect the integrity of an investigation or the juvenile’s privacy,” wrote McIntyre, who is a member of CFOIC’s board.

“So what was going on here? It’s pretty clear the city attempted to use a law designed to protect juveniles’ privacy to protect adults who were accused of wrongdoing, and a department that was accused in a use of force complaint. Some of those adults still work at the police department.”

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on X (formerly Twitter) @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.